An Autumn Duck Flight

The sun had gone down in a blaze of golden glory; I stood on the edge of the marsh in the crimson afterglow which painted the long marsh pools and open ditches with streaks of flame.

The marsh stretched interminably inland to be lost in the eddying white of a rising ground mist before it reached the hedged fields of civilisation.

I might have stood on the threshold of some primaeval undrained fen; the clock might have been turned back hundreds of years, and I, a primaeval hunter dressed in bearskin with a wolfhound at my feet instead of a very imaginative flight shooter with a twelve bore in the crook of my arm and a spaniel at my heels.

The marsh was old and wide, the brown of the rushes was brought into high relief by patches of bright green where the cattle had cropped the coarse grass almost to the texture of a lawn. The pools were mirrors reflecting the pageant of the autumn sunset, their faces undisturbed, except where a moorhen swam jerkily across leaving an ever widening V of tiny wavelets to ripple on the reed-stems at the edge. The feathery tops of the reeds bowed like aristocrats at court balls before the faintest of breezes, which failed to mar even with the gentlest ripple the glass like surface of the water.

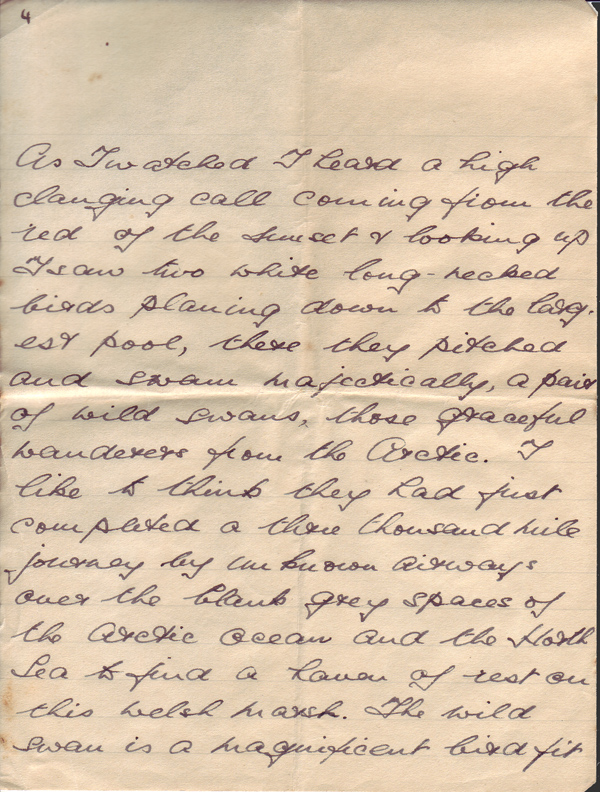

Moorhens croaked; coots clanked; mallards quacked and splashed somewhere in the dense wilderness of the reedbeds; redshanks whistled restlessly over the length and breadth of the marsh, darting here and there on fluttering wings, never still. As I watched I heard a high clanging call coming from the red of the sunset and looking up I saw two white long-necked birds planing down to the largest pool, there they pitched and swam majestically, a pair of wild swans, those graceful wanderers from the Arctic. I like to think they had just completed a three thousand mile journey by unknown airways over the blank grey spaces of the Arctic Ocean and the North Sea to find a haven of rest on this Welsh marsh. The wild swan is a magnificent bird fit to be admired, an adventurer as old as time.

A sibilant whistle of pinions in the sky above, that sound which holds half the romantic mystery of wildfowling in its grasp, served to remind me it was time to move as the ducks were starting their flight inland from the sea.

I made my way to “The Willows” which was a butt on the edge of a dense reedbed with sixty yards of open water in front.

I stood in my butt and listened to the mournful wailing of the green plovers, the piping of the curlew, the scraping of snipe as they swished about the sky and dropped with tiny plops on the water’s edge, and all the various sounds and bird notes that make up the entrancing and ever fascinating wild chorus of the marsh. I had no great expectations of the flight as it was too still and the ducks would probably come in high and “dive bomb” the pool.

I had not been waiting long when there was a swish of wings overhead and three teal appeared from nowhere. I took a snap at one as they went past, the shot was followed by a splash. I sent the dog for it and he came back with a beautifully marked drake, the smallest and prettiest duck in England. My next shot was at mallard as five of them came in high with their wings whistling and the drakes quacking softly, they circled the pool coming lower and offered an easy chance of a right and left which I missed quite inexcusably. Most of the ducks were passing over, the mallard probably bound for the stubble fields, while the widgeon appeared to be going to the other end of the marsh. I could hear them passing high, the whistle of the drakes and the piercing growl of the ducks, that musical chorus which stirs the shooter’s blood, came clearly in the still evening air. A pair of shoveller came over just in range and I dropped them right and left into the reedbed behind me. Toddy went off to look for them and came back proudly with a rat he had just caught, eventually he brought back both birds, a duck and a drake.

After a long wait nothing more came so I gave it up. As I walked home in the gathering darkness a big orange harvest moon like a lantern was just rising, two brown owls were calling to each other in the vastness of the pinewoods on the right, with that soft, clear hoot that brings back memories of moonlight nights in summer.

As I stood on the edge of that marsh it seemed like a dream with Holyhead only ten miles away. There is definitely a whisper of the primaeval days on that marsh at a time like that. You cannot kill these things at night.

By Hugh Tetlow